28 Days Later: Hypnotic, Dreamlike, and Mind-Boggling Visual Storytelling

SPOILERS!

At the time, this Danny Boyle feature film inspired by the Foot and Mouth disease outbreak in England during the early 2000s was one of the most frightening yet tranquil zombie films to come out of any director in the 40 some odd years that the zombie genre had been born. Even nowadays, its fast-paced and shaky-cam style of directing during tense moments of action scare the living hell out of me, but I can’t help but notice a dream-like quality the movie has in its downtime, with beautiful scores accompanied by shots that you can barely wrap your head around. These scenes, usually imposed over beautiful hymns and symphonies such as Abide With Me, Ave Maria, and Requiem in D Minor add a beautiful and hopeful undertone to such a nightmare-like scenario.

In fact, one of the most iconic sequences in cinematic history of an abandoned, desolate London stems from this very movie. Ravaged by the consequences of cruel psychological and physical experiments on chimpanzee test subjects, London, along with the rest of the world, is thrust into an apocalyptic world where the Rage virus travels from person to person, transforming an otherwise ordinary human into a blood-hungry beast within a matter of seconds of contact with infected blood. Waking up from the hospital after a coma-inducing bike accident nearly a month after the initial outbreak, Jim, our protagonist, finds himself entirely alone in one of the most bustling cities the 21st century has ever seen. These shots are truly haunting and stunningly demonstrate the potential a pandemic has to entirely recalibrate humanity and its habitats, especially one as deadly as the fictitious Rage virus. This also includes an absolutely chilling shot of Jim looking around for any signs of life while Big Ben stands tall in the background. Without hindsight of how these shots were done, how all of London, it seems, could be cleared out for a number of shots in the beginning scenes of a movie, helps the audience to think about and reflect on the absolute scale of Jim’s surroundings and situation. It helps the audience better relate to Jim whilst also delivering an unbelievable sequence. These shots after Jim wakes from the hospital also have a bloom filter, further metaphorically and literally blurring the lines between dream and reality.

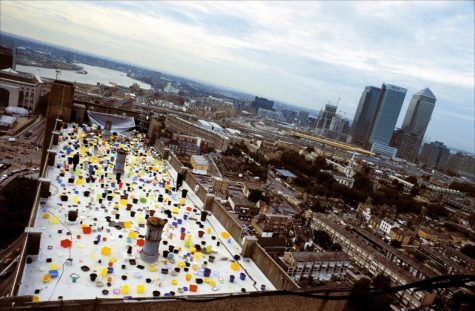

After realizing that something clearly wrong has happened, Jim walks into a church and gets chased down back into the streets of London by the infected. It is here when he meets Selena and Mark, two other survivors who ward off the horde and help Jim find his long-deceased parents. After an attack where Mark dies (RIP Mark), Jim and Selena travel around looking for food, weapons, and other survivors when Jim notices a flashing light high up on an apartment high-rise complex. After making the treacherous journey up the innumerable flights of stairs, a former cab-driver and his daughter take Selena and Jim into their home. After spending the night, Frank, a lovable father figure to the ragtag group of survivors, brings Jim to the roof of the high-rise to show how him and his daughter Hannah have been getting by for the past month. The way is through setting up countless buckets on the rooftop and waiting for rain, and the visual of the brightly colored buckets forming a sort of technicolor wasteland with only Jim and Frank to bear witness to is almost hypnotic. It buries an overwhelming sense of isolation with the vacant city in the background, barren and cold. Mixed with the incredibly fast-paced sequences of action in scenes with infected, these relaxed and mostly quiet shots force the audience to reflect on how lonely, horrifying, and dreadful the given situation for these relatable characters really is.

In a moment of potential hope for our survivors, Frank tells Jim and Selena of a repeating radio broadcast pleading for other survivors to come to the Forty-Second Blockade on Manchester for “the cure to infection!” The man in the message claims to have set up a military base on the blockade and urges others to come and take refuge with him and his men. Jim and Selena both agree to take the trip and one of, in my opinion, the best sequences in the film takes place. Set to the tone of Ave Maria, this awe inspiring scene shows our group driving in the forsaken streets of London. On their drive, an oddly familiar image appears, as the group drives on a curved road with huge wind turbines in the background. It really feels as if it is ripped straight from a dream and is something that we would now call a liminal image. If you aren’t familiar with the idea, a liminal image is often associated with liminal spaces (transitional spaces). The word “liminal” is derived from the Latin word “limens,” which means threshold. When you view a liminal image, it can feel as if you are interacting with or on the threshold of seeing two separate realities interact with one another. I.E., something out of a dream and the real, moving world. Liminal images often make us uncomfortable and dissociate, which is why it is so perfect in this movie about an apocalyptic world in ruins.

Then, after a trip at an abandoned grocery store to stock up on food, a visual reminiscent of a dream slowly comes into frame. As our heroes drive towards sanctuary in this transcending and relieving scene set to Requiem in D Minor, the shot pans up to the entirety of Manchester in flames. Explosions erupt soundlessly from the horizon as Jim repeats to himself, “The whole of Manchester. The whole city.” From their dialogue and the unbelievable sight, it seems that in their shoes it would be hard to discern and break down the sight before them, making it more believable to think that they are simply dreaming instead of facing the horrible truth.

After a devastating scene where our characters get to the vacant blockade, Frank gets infected blood in his eye, becomes infected himself, and is quickly taken care of by out of sight military men in camo fatigue. Our remaining three survivors are taken in by a group of eight soldiers and their general; Major Henry West. These boys have taken over a mansion. They have set up a high security perimeter with landmines and tripwires tapped to explosives that warn them of any horde invasion. They have high power weaponry at the ready, including bayoneted weapons and mounted machine guns atop the many balconies. They even have a water heater!

What they don’t have though are women, and Major Henry West promised his men to attract survivors via radio messages to bring women and repopulate. Of course, the only women there now are Selena and Hannah, so Jim, after learning of the boys’ true intentions, attempts to escape from the mansion with his companions. He gets bonked on the noggin and sent to be executed so the men can have their way with the women. Jim miraculously escapes being executed and slowly kills off all of the military men one by one and breaks Selena and Hannah out. They escape in Frank’s car and find refuge in an undisclosed location somewhere far away from any potential infected threat. Now, I know I keep saying, “in one of the (insert certain good attribute about a scene or shot here) of all time,” but this specific shot that flashes on screen in a choppy and tense moment where Selena is attempting to revive Jim after being shot in the chest by Major Henry West moments before their final escape from the mansion (forgot to mention that, whoopsie) really is the single best shot in any movie I’ve ever seen. This specific shot is the whole reason I decided to write this article in the first place. It is gorgeous, following the rule of thirds in photography by having the piercing white letters of “HELL” in the top left corner. In my opinion, it perfectly fits in the wedge between a dream and reality, visually confusing as the landscape is upside down while the text is right-side up. It doesn’t make sense and that’s the whole point, as it makes the audience, or at least me, pause and reflect on its perplexity. I haven’t been able to get this shot out of my head, so I hope you can at least appreciate its cinematic beauty.

In a messy conclusion, I really love 28 Days Later for its unique directing style, transcendent message, and stunning visuals. They really make the movie, and I didn’t even discuss the horror and complexity of the infected attack scenes that make this one of the scariest zombie films of all time. Even the inspiration for and story of this movie is partially relevant to the times we are living through right now. Some may say that an empty London wouldn’t be so far fetched in 2020, and they would be right. It is just another reason why this movie isn’t just another horror movie, but a social commentary on how people live through and find happiness even in the worst of times. From Jim and the gang riding their carts whilst shopping for free in a forgotten grocery store to the soldiers finding enjoyment out of seeing an infected bounce from landmine to landmine, our happiness reflects how we approach any given situation, not the situation itself. Regardless, this all shows me that this movie is a lot more than what it seems on the surface, and I would strongly urge you to *legally* watch it if you are interested at all. Maybe you could discover a subtext that I haven’t quite caught on yet.

Erick Hardy • Dec 16, 2020 at 8:34 pm

Great article Preston! I have heard of this 28 days later before, but I have never watched it. It sounds like a great movie that I might have to check out. Keep up the great work.

Rochelle Pense • Dec 16, 2020 at 12:24 pm

Amazing article! I love how in depth you go, and the passion behind writing this. I’ll be honest, it was kind of hard for me to wrap my head around at first, but now I wouldn’t mind watching it. Keep up the great work Preston!

Madison Cummins • Dec 15, 2020 at 10:09 am

This is such an incredible article Preston! Even though I have never seen this film myself, reading this made me interested in wanting to see it. Keep up the amazing work!

Jack Salyers • Dec 15, 2020 at 8:31 am

What an amazing article Preston Parker. I enjoyed reading this article and may end up watching this film in the future. Keep up the great work!

Olivia Packard • Dec 15, 2020 at 7:54 am

You did really awesome with this article Preston! I am not really much of a movie watcher, especially with these kinds of movies. But you made it sound interesting! Keep it up!

Bella Panmei • Dec 14, 2020 at 12:15 pm

I always enjoy reading your reviews and I think you did a very good job portraying it. The way you presented the movie really makes me want to go watch it tonight. The whole plot of the movie seems rather intrigueing and I can not wait to dig into it. Keep up the great work Preston!

Nathaniel Wayne Moss • Dec 14, 2020 at 11:36 am

Great article! Very well written and I loved the amount of details you put into this. I really enjoyed this article I didn’t know anything amount any of this. Keep up the great work!